|

Arthur

"Archie" Ament on the left, with Earl Shellenbug? on right. Photo

compliments of the Elmira ON Legion and the Elmira Photo Lab. Reproduced with the

permission of Archie's daughter, Myrna Ament.

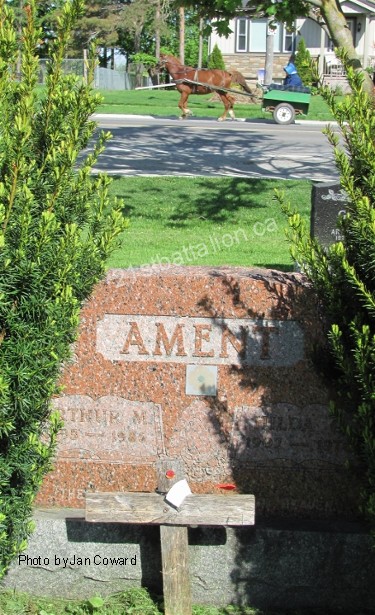

In a prominent place in the Elmira Ontario Legion Branch 469 Memorabilia Cabinet is a

picture of Arthur Ament, a World War I soldier. This picture is particularly dramatic as

it shows a young man in Lens France supported on crutches and missing a leg. Although his

picture is in our Memorabilia Cabinet, there was little information available about

Arthur. His daughter Myrna came into the Branch on Dec 14, 2000 and gave a history of her

father.

Arthur (nicknamed Archie) was born on Feb 12, 1895 in Britton Ontario and later, when he

was 5 years old moved to Linwood. His father was a brick layer and stone mason and Archie

grew up in a family of 5 with brothers and sisters. During his teenage years, Archie was

athletic and played football and speedskated. In fact, just before the war, he had a

yearning to join the then famous Ice Show in Toronto. After he completed school, he worked

in a retail store in Linwood and later obtained a job in Krug's retail store in Tavistock

selling drapery and carpeting.

Archie joined the 168th Oxford Battalion on Feb 23, 1916 as a Private and his service

number was 675617. On Nov 17, 1916 he was promoted to the rank of Corporal. He was

transferred to the 21st Battalion on Feb 2, 1917 and was promoted to his final rank of

Lance Corporal on Sept 28, 1917.

Archie was officially discharged after the war on May 15, 1919 and went to school in

Toronto from Sept 19, 1919 to May 20, 1920 to further his education. After this, he became

the Linwood Postmaster and remained there until his retirement in 1959. It is assumed that

he belonged to the Linwood Legion Branch and later transferred to the Elmira Branch in

1961 as a result of the Linwood and Elmira Branches amalgamating.

Archie married Hilda Rosger in 1928. Hilda's father owned the hotel in Dorking which was

located on the South East corner of the intersection. Hilda and Archie had a son Glenn and

a daughter Myrna and these children were raised in Linwood. Both Glenn and Myrna now live

in Waterloo. After retirement, Archie moved to Waterloo and transferred to the Waterloo

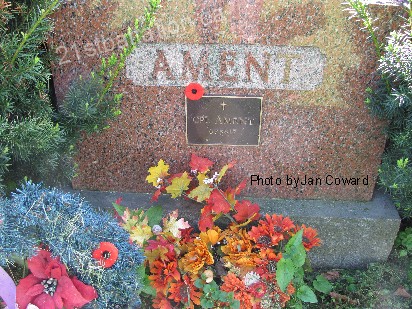

Legion Branch in 1974. Archie died on Dec 1, 1986 at 91 years old and was a great great

grandfather.

Archie would never talk about his experiences in the war to his children until after his

ninetieth birthday when Archie narrated the following to his daughter Myrna:

The "Great War" as it was then called, broke out when I was working in

Tavistock. I and eleven other young men went to Woodstock to join the army. I have a

picture postcard of the group entitled "Tavistock's First Dozen". My mother had

not heard from me for several weeks as I was no longer in Tavistock to receive and answer

her letters, so she sent someone to inquire about me. Mr Krug, my former employer told him

that I had left to join the army. This news was quite a shock for my mother.

We were first stationed in the Woodstock armouries. Our first march was to Wolsely

Barracks in London, a distance of forty miles wearing a full pack weighing 90 pounds. In

the army units, there were many bands that always accompanied us on our march. We were

encouraged to sing along with the familiar tunes. Needless to say, many of the words were

improvised and not suitable for singing while on a public march. We had an overnight stop

at about the half way point and were billeted overnight in private homes. I and one other

soldier were billeted at a doctor's home, were fed a sumptuous meal, and the meal was

served complete with crystal, linens, and silverware. We were surprised, impressed, and

honoured.

We received several weeks of "basic training" in Canada before sailing to

England. We sailed on a ship called the Lapland on October 19, 1916 and arrived at

Liverpool. In England we received several more weeks of training before being sent into

action. In England, we were stationed in tents on the Salisbury Plain. We were always damp

and cold. Back in Canada, we had much colder temperatures to contend with, but not the

same degree of dampness. The first while in England, I spent my leaves exploring London's

Madame Tussaud's Wax Museum, Piccadilly, and other places. I was particularly impressed

with the highway structure, especially the roundabouts (clover leafs) that were three

tiered. These did not exist in Canada until many years later when they were constructed in

Toronto.

We were first sent to France on May 3, 1917. Every time we went to France the Ocean

channel was choppy and many of the troops became seasick. When we were sent in fresh from

England, or from leave on the continent, first we would be assigned to the front line for

three days, then the reserve line for three days, then the support line for three days,

then behind the lines for a rest. Then this procedure would be repeated, however, this did

not always hold true, as sometimes we would lose too many men at the front and

replacements were not always available to relieve us.

Our rations were another "iffy" situation. We never knew if it would be a feast

or a famine. Some days, especially during heavy shelling, our rations could not get

through to the front. Other times when we had many casualties and the rations did get

through, we had double and sometimes triple portions. Every morning when we were in the

trenches we were given a shot of rum, not being much larger than a thimbleful. If you

could swallow it and immediately say "Thank You" you qualified for a second

shot. This rarely happened as you could feel it down to your big toe and by this time the

potion rendered you unable to speak.

A friend of mine had given me a stainless steel polished rectangle 3X5 which could be used

as a mirror. It was engraved with my name and regimental number on it and I always kept it

in my left tunic pocket. When there was a lull at the front and we could shave, I would

prop this "mirror" up in a suitable place. One day, as I was shaving, a bullet

hit the mirror knocking it down. I still have this nicked "mirror".

I was always particular regarding my appearance. I had a dress uniform made to measure and

kept it safely in London to wear on leave. One morning in France, we were called out for

dress parade. I was called out of line for being the best polished soldier on parade. When

asked to show my ID tags, instead of being around my neck, I had them in my tunic pocket.

I always kept them in my pocket because the lice would congregate on the strings that

showed around your neck, and I could not tolerate the appearance of them. Needless to say

the honour of best dressed soldier on parade went to another soldier.

While serving in France, my duties were many and varied. To name a few I did mail

delivery, rum running, Military Police, stretcher bearer, machine gunner, and burial

detail. At mail call I would pass out the mail to the recipients. This would be a very

happy time for some but disappointing for others. If any mail was addressed to a soldier

with a German name, I was ordered to route this mail to a censor.

I took a special course in bayonet training which was crucial in hand to hand combat. We

were taught, if need be, to thrust the blade into the opponent and give it a half turn

before withdrawing. I kept my rifle in A1 condition as we were told that at the front,

your rifle is your best friend.

The noise at the front could be deafening. From the stress of this, occasionally a soldier

would go berserk and start shooting at anything that moved including his own trench

comrades. On rare occasions this soldier would have to be shot for the safety of all. This

behaviour of the individual was known as "Shell Shock".

My duties as Military Police mostly consisted of bringing the AWOL back to the lines.

Sometimes this would involve a two day journey each way. Needless to say there was no

sleep once the prisoner was apprehended until he was safely delivered back to

headquarters.

For certain offenses, a "court martial" would be conducted near the battle

sites. If the charges brought against the soldier were proven and he was pronounced guilty

and sentenced to death by firing squad, this sentence was usually executed immediately. I

suppose to ease our conscience, we in the firing squad were told some of us were given

blank ammunition.

One night while on the move in France, we came to a farmer's barn. We decided to spend the

night there under cover sleeping in the haymow. To our delight, there was a whet stone set

up in the barn and we all sharpened our bayonets. There was also a supply of turnips in

the barn. These were readily devoured as we hadn't eaten since the previous morning.

The trenches were always wet, with about 6 to 12 inches of water on the bottom. Many

soldiers developed a condition known as "Trench Foot" as a result of constantly

standing in the water. This condition could be quite serious and sometimes necessitated

the amputation of the feet. I usually stood on a ridge built into the wall of the trench

called the "firing step". This had its advantages because at least my feet were

dry. The step also had disadvantages because I had to be in a crouched position so that my

head could not be seen above the trench and be a target for the enemy.

The Salvation Army was good to the troops, setting up stations in dugouts close to the

front. Here you could sit and write a letter home, have some friendly conversation, or

relax and have a cigarette and hot chocolate. They also had barrels of chocolate bars and

always a supply of dry woolen socks. The Red Cross also supplied the boys with socks.

Canada did not have military conscription until an act was passed in 1917. While in

France, we soldiers were given the right to vote on this issue.

The trenches were overrun with rats that would feed on the corpses. We shot many, many

rats. We always said that the purpose of the putters was to deter the rats from crawling

up your legs.

Depending on the wind direction, we were aware of the possibility of a gas attack and were

issued gas masks. These consisted of several components to be assembled for use. Previous

to this we had a flannel bag to be worn over our head, and were also instructed if need be

to urinate on our handkerchief and place it over our face. The gas would burn our skin and

I have scars on my body because of it. When a grenade would land in the trench, we would

quickly pick it up and toss it back into the German trench. Sometimes this was not done

successfully.

At Passchendaele, I was a stretcher bearer and this was a messy muddy assignment. Due to

the mud, it was necessary to have four bearers for each stretcher. We were instructed to

check the wounded periodically on the way to the dressing station, and if they had died,

to roll them off at this point and return to pick up someone else. While transporting the

wounded in the trenches, depending on the degree of turn in the trench, we would have to

raise the stretcher above the trench to make the turn. Often the wounded soldier was

targeted by the enemy and killed this way. Sometimes there were so many dead, it was

necessary to walk on the bodies. Depending on the state of mutilation or deterioration of

the corpse, the flesh would give way under foot, and you would slip and fall.

Burial detail was not as dangerous as some of the other duties, but it was more

depressing. We would dig a rather shallow trench, remove the IDs and any other valuables

from the bodies, then roll the soldier into his blanket, then into the trench, and refill

the trench. The IDs and other valuables were catalogued to be sent later to the next of

kin. If we were unable to bury the dead at the end of the day, due to continued shelling,

we would pile them like posts, until a time was available for a mass burial. Our Chaplain

always presided over these burials.

Because of the mud, we had to build many duckboards. These consisted of two long pieces of

wood with crossboards nailed to them at fairly close intervals. These were laid on top of

the mud to facilitate the transporting of supplies to the front. We mostly used donkeys

and carts for this purpose. I have seen donkeys with stomach wounds and their intestines

hanging out to the duck boards. Their back feet would step on the intestines, pulling them

out further with each additional step. These donkeys would have to be shot. If a donkey

stepped off the duck board and became mired in the mud and couldn't be freed, it also was

shot.

Sometimes at night, our officer would ask for a volunteer party to go into "No Man's

Land", the area between our and the enemy trenches. I went on several of these

forays. We would form a V, much like the pattern of geese in flight. We crawled on our

stomachs and had to be quiet, often not moving for several minutes. When we resumed

moving, each man was to be sure the man behind him was following. One night, I was the end

soldier on one line of the V. I fell asleep and didn't hear the order to move on, which

was always whispered. When I awoke, I was alone and had lost my sense of direction. I

crawled cautiously until I heard German voices and quickly realized I had to reverse my

direction to get back.

Sometimes in the evenings, another soldier and I would be sent to the supply depot to

bring the rum up for the following morning. We would each be given a shoulder yoke with a

sealed stone jug of rum on each end. These jugs were fairly heavy and on one such trip,

the seal of one was broken. We decided to sample the rum on the way back to the front. It

was potent rum and needless to say, we were feeling no pain when we arrived at our

officer's post. I went in and announced the safe delivery of the rum. The officer looked

sternly at me (I was shaking in my boots) and he said "Ament, would you like a little

drink?" and broke into a smile. The officer was E.J. Glasgow and he was a fine man

who did not smoke or drink. He wouldn't order a man to go where he himself would not go.

He was wounded in 1918 and died of his wounds. There is a statue likeness of him at

Morwood near Ottawa where Remembrance Day services are held each year.

I clearly remember the night my best friend Harold Fraser was killed. The next morning I

found his body. It was pierced like a pin cushion, riddled with bayonet stabs. I removed

his Masonic ring and watch and personally sent these to his parents. When this bloody

fiasco was over and I returned home, his parents wanted me to visit them but I never did.

I just couldn't face them and answer the questions that they might ask. I suppose they

thought ---- what kind of friend was this!

At the beginning of 1918, we were hopeful that the war would soon be over as we noted that

the prisoners we took were either young boys or old men.

At certain intervals, we were given ten day leaves. I would always go to London, but later

(1918), I would go to Edinburgh. My first stop was London to pick up my dress uniform,

then to Victoria Station to board "The Flying Scotsman" to travel to Edinburgh.

Food was not plentiful and I remember going to two restaurants for a full course meal in

each, before I felt I had enough. I would book accommodation in a hotel and would try to

sleep in the bed. I always ended up sleeping on the floor as the beds were too soft and we

were not accustomed to that type of pampering.

Just before I was wounded, I had a ten day leave which I spent in Edinburgh. Since the

leave was near to the date of my twenty third birthday, I celebrated by having a

photograph taken to mark the occasion. Then it was from there to London, then back across

the channel to France that night, to go into the front line in the morning.

When I arrived back at camp that night, there were thirteen letters and five parcels

waiting for me. I read the letters and opened the parcels of gum, canned goods, sweets,

cigarettes, and several pairs of hand knitted woolen socks. I put one pair of socks on,

one pair in my duffle bag, and passed the others to those in need. All that night I had an

uneasy feeling, I dozed fitfully, considered going on sick call in the morning, but

believed I was recorded as never having gone on sick call. I wanted to continue this

perfect record, and just being back from leave, well fed, and rested, I decided to

"stand to". This particular morning of March 4, 1918, I was assigned to machine

gun duty and with 16 men under my command, was ordered to hold the position.

The enemy raided the line at 5:55 AM and the shelling was furious. At one time I looked

around and counted only eight men and myself. Some had been killed and others had ran.

Next time I glanced around, there was only one man and myself. I remembered my orders to

hold the position but a large shell fell short of the trench and buried itself in front of

me. The shell exploded throwing me about forty feet away. While lying on the ground, I

looked at my leg. It looked like chopped liver, very elongated but still attached to my

body by a slender sliver of flesh.

A buddy of mine was on stretcher duty this particular day and he knew the position I was

assigned to, so he came and picked me up and transported me to the coast and across the

channel to an English hospital where my leg was amputated leaving only an 8" stump.

It was touch and go whether my other leg would be amputated but thankfully, it was saved.

The hospital room had twenty-four beds filled with wounded men. Since I was the first bed

to the left of the door, I was served first at mealtime. As I recovered I became hungrier

and after the meals were served all around, the nurse would ask me if I wanted another

plate. More often than not, I accepted the invitation.

As I became stronger and mastered the art of walking with crutches, I was allowed to leave

the hospital for several hours each day. We had free access to public transportation so

could go sightseeing all over London. Many people would ask us into their homes to have

meals. Sometimes, myself and some others from the hospital would go to Liverpool to watch

the American troops coming in. Some, as they came down the gangplank would say "What

have you guys been doing all this time?? We're here now so the war will soon be

over". Some were quite arrogant so we would retaliate by saying "The bugle blew

in 1914 and you just heard it now??".

Finally in Sept 1918, we embarked for home on a hospital ship. Instead of bunks we were

assigned to hammocks. I believe this was to minimize the incidence of sea sickness. Some

of the wounded died on the passage home and were rolled into their blanket, weighted,

tied, and buried at sea.

When I arrived home in Linwood, a large crowd complete with a band welcomed me at the

station. I was presented with a gift of money with which I purchased a leather club bag. I

was later told that everyone donated toward this presentation for me except one person who

said "He didn't have to go to war. Let the SOB work to earn his living!"

Clayton T Ash

Royal Canadian Legion

Elmira Ontario

December 22, 2000

|