|

Q

|

We are talking this

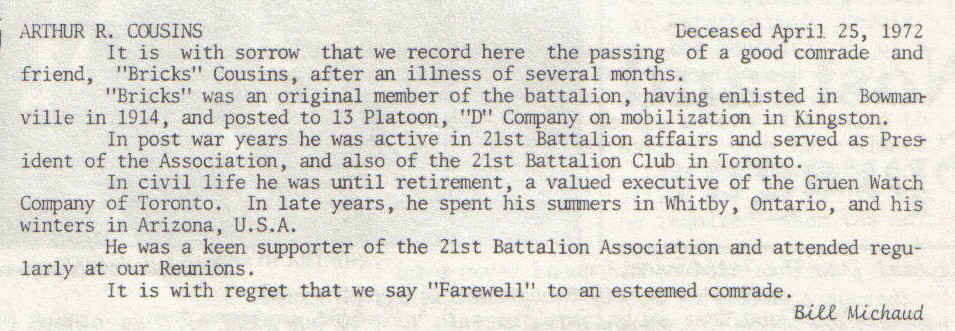

evening with Mr AR Cousins who, in the First World War, was with the 21st

Battalion

|

|

A

|

In Kingston. We were around there for about a week or so and

then they formed the 21st Battalion which they had planned before. We got out of these old uniforms and into the

khaki and then made up the company with a group from Ottawa, Cobourg, Peterborough and all

down through Eastern Ontario. They made us

up into eight companies and that made the 21st Battalion

|

|

Q

|

This period in

Kingston, were you able to be accommodated?

|

|

A

|

The second half of the

battalion, we were in a cereal building, an old cereal building up on the waterfront.

|

|

Q

|

You mean an old –

|

|

A

|

Where they stored

cereals, grains of different kinds, a kind of an elevator but it wasn’t actually, it

didn’t have the pipes or anything. I

don’t know just what they kept in it. It’s

still there.

|

|

Q

|

A great smell, a place

like that?

|

|

A

|

Yes, but we soon got

rid of that. They put four bunks high in

there, you see, and put us in there and they had the dining room on the main floor and the

canteen and then fenced it in. It was right

beside the locomotive works. We walked right

out to the pier, you see. We used to do

our physical exercises there in the morning, have breakfast and then the boys would go up

to the park in front of the law courts to do our drill, a lot of it, on grass.

|

|

Q

|

I know that location

very well

|

|

A

|

Then we went to the

barracks of course where the armouries are now. The

right half of the battalion were over there and we used to go up there and join them and

then do our battalion drill and, of course, we walked up and down Princess Street enough

to be called the Princess Pets. We got that

all the time. Our Colonel, of course, was

William St Pierre Hughes who was a brother of Sir Sam, you see, and we got a lot of

roasting about that. Anything that we did

that somebody else didn’t get was because of the brother.

|

|

Q

|

Was there a lot of

controversy about Sir Sam Hughes, do you recall?

|

|

A

|

Only on account of the

rifle, you know, the Ross rifle.

|

|

Q

|

Was it a good rifle,

did you have it in the beginning?

|

|

A

|

It was lovely for

target shooting, it was wonderful for that but, under rapid fire, I remember at Messines,

in fifteen minutes there wasn’t a gun that would shoot, in fifteen minutes. If Jerry had come over then he could have waked

right through us, we didn’t have a defence except the bayonets.

|

|

Q

|

Now, let’s not get

over to Messines. Let’s hang on a second

and find out what happened there at Kingston. Were

you well up to strength? Did your battalion

begin to achieve some morale there?

|

|

A

|

Oh yes, we put on some

great shows there and got our Colours there, you know, and our relatives all went down

there for a big “At Home”. We were

going overseas, you see, any week, any day but we were there all

Fall and all Winter. We didn’t leave there until May and we were

disgusted.

|

|

Q

|

May of 19-

|

|

A

|

1915. We didn’t think we were ever going to get

over, we thought the war was going to be over before we got there.

|

|

Q

|

Did the 21st

Battalion have any other name?

|

|

A

|

No, now our unit is the

Prince of Wales Light Infantry of Kingston and they’re still in existence and they

have our Colours in safe keeping down there.

|

|

Q

|

You never did get a

nickname like “The Mad Fourth” or anything?

|

|

A

|

No, we had “The

Fighting Two and The Dashing One, The Dashing One and the Fight Two”. No, The Fighting Two and the Dashing One. No, we didn’t have, like the VanDoos, you

know of the 22nd. They were in our

brigade, you see. They were really an

excitable bunch, they always started something wherever they were.

|

|

Q

|

You were in pretty

close contact with them too?

|

|

A

|

Oh yes, the 19th,

21st and 22nd were in the one brigade.

|

|

Q

|

Did you get along well

with the French Canadians?

|

|

A

|

Oh yes, fine, lots of

fun.

|

|

Q

|

I’ve always heard

that.

|

|

A

|

Of course we had a lot

of French Canadians with us too, you know. We

had a company from Ottawa which had a lot of French fellows in it and I was surprised. Mind you, they were all good-hearted fellows. I got along well because I was only a kid from the

bank. I wasn’t very rough, you know, and

they helped me out an awful lot, a lot of things they did for me, for instance, I always

traded my rum issue for their jam because I didn’t like rum at the time. In Kingston, we were there as I said until May,

and then we got going.

|

|

Q

|

Did you go as a

brigade?

|

|

A

|

The 20th and

19th were there in Sandling when we arrived.

We went over in single boats, we didn’t go over as a convoy like they did

later or like they did in the last war. We

mounted machine guns on the Metagama. We

went over on the Metagama with a unit of medical people form Montreal and we mounted the

machine guns on the deck. Of course I doubt

very much whether they’d have done much good but they were there.

|

|

Q

|

At least you felt you

had something.

|

|

A

|

Sure, we had something.

|

|

Q

|

Anything eventful

happen?

|

|

A

|

Not at all, not at all. We got over there and never saw a thing.

|

|

Q

|

Pretty boring for

troops on a boat.

|

|

A

|

Oh yes. We had boxing matches and that kind of thing. A lot of the boys got seasick but we didn’t

mind it, I didn’t mind it at all. We got

over there and it took us about ten days.

|

|

Q

|

I suppose this was the

first time you’d been away from Canada.

|

|

A

|

No, I’d come over

here, you see.

|

|

Q

|

You’re British

originally?

|

|

A

|

Yes, I’m British

but I was born in China. My dad was a

missionary over there. I didn’t come to

Canada until I was eight.

|

|

Q

|

Now, let’s see, we

got you to Sandling and there is the brigade forming up.

Did you have any instruction coming in from troops or were you entirely on your

own?

|

|

A

|

We were entirely on our

own. We had some First Division fellows who

came and helped us in training, you know, and we were all in Sandling, the whole brigade. In fact the whole Second Division was made up then

in England, you see. I’m not quite sure

where they all were. Some were in Bramshott,

I think Our brigade was in Sandling

just outside of Folkestone. Folkestone or

Hythe was the place we went. The beer in

Hythe, that’s where I was introduced to drinking beer.

I’d never had a drink of beer before in my life before I got there. These fellows going over, you know, all Englishmen

you see, were telling us about the wonderful beer they had over there and they were dying

to get hold of some this beer so the first thing we did was march down to Hythe to see

what the beer was like and it was good. I can

remember I had one pint and I really felt it, as a kid you know.

|

|

Q

|

I think drinking beer

like that the first time, you really have to learn. It

takes a little while.

|

|

A

|

No, I wasn’t too

fond of it. Well, we had from May until

September in England in training. I

didn’t see too much of it though because was Company Clerk and I kept the Company

records so I was in the office an awful lot but I did get some training.

|

|

Q

|

You’d got to be an

NCO?

|

|

A

|

No, they wanted me to

be one but I didn’t because I was too much of a kid.

I didn’t think it was right, it would look funny. We were inspected by the King there and by

Kitchener and we had a sham battle. We

marched on and took Ashford one day. In

fact when we were back in Kingston we marched from Kingston to Gananoque one day and were

entertained by the ladies of the churches down there that night and then walked back the

next day, marched back the next day. That

was tough.

|

|

Q

|

So, in September you

got across the Channel

|

|

A

|

Yes, we marched from

Sandling to Folkestone and boarded a tug or a small boat there and we got in pure rain,

just raining cats and dogs. We got soaked. When we got on, we couldn’t sit down, we had

to stand up there were so many of us. There

was no room to sit down so we stood up. We

got about halfway across when a destroyer came along and turned us back. They said there were subs around or something so

we had to go back until daylight and we stood or sat or leaned or whatever we could till

morning, till daylight, and then we went over to Boulogne and they put us up on the hill

at Boulogne and let us lay down and dry. Boulogne

was very nice but it was up on a hill. I

remember going up, the ladies or the women of the town were all out on the side offering

beer and wine to us.

|

|

Q

|

Later on they

didn’t do that but they were still doing it?

|

|

A

|

Yes, they were doing

then. We got up there and to dried out and

then they marched us down to the railway and put us on the train and we went to St Omer

from there by train in boxcars. We got out

there in the middle of the night I think it was and we marched from there right up the

line.

|

|

Q

|

You don’t mean you

went right in?

|

|

A

|

No, we went to Tenouse

(?) which was about five miles back.

|

|

Q

|

So you were in reserve

really.

|

|

A

|

We were in bivouacs. It was a very quiet part too opposite Messines. It was quiet because our fellows were laying mines

under Messines at the time and they didn’t want ay disturbance, you see, while they

were working so we got our kind of initiation right ere.

We went up a few days later.

|

|

Q

|

I wonder if you can

remember, I’m always interested, you know you enlist in Canada as a green boy, a bank

man, and you’re in the army. You know

you’re going to be in a fight, you know you’re going to be in a war when you go

there. What happens the first time

you’re really there? I remember very

clearly what happened to me in the Second War and I’m always interested. Do you recall what it was like for the first time

you were ever near to getting in the war?

|

|

A

|

At Messines I

don’t think that we had too much there. I

think we thought it was kind of easy because there was no real action. We had one fellow killed there but by a stray

shell or bullet outside and he, by the way, was the only man that we built a coffin for. Our, what did they call them, pioneer department

built him a box out of pine but he was the

only man we ever had any time for. Down at

Messines, not until we got to the M ad N which was our next move in about a month, we went

down to the M and N which is in Belgium right near Ypres, south of the Salient, Ypres

Salient, we went in there and then we ran into a bit of trouble there.

|

|

Q

|

By M and N you the

trenches? I’ve heard about it before, I

just wanted to quite sure.

|

|

A

|

Ridgeway was the town

and Ridgeway Woods. La Brasserie was our

medical centre and then about a mile up this duck walk to the trenches and we had those

with some redoubts. We looked after those for

the whole winter, through the winter till they flooded us out in the spring.

|

|

Q

|

No moving about, you

just were there for the winter?

|

|

A

|

We stayed there, yes. That must have been three months.

|

|

Q

|

You would manage, I

suppose, during that time to get yourselves dug in?

|

|

A

|

We had some very nice

trenches there, not as nice as the Germans but they were very comfortable.

|

|

Q

|

I’d like to ask

you a little bit about that. In say your own

case, in those dugouts built in the side of the trenches, were there two or three men in

there? What was it like? Do you remember who they were and how you got

along? How did you make food? Can you say anything about daily life in that

situation?

|

|

A

|

They tried several

ways, you know. At first they tried making

the food back in community kitchens and then we had cooks working but invariably

they’d get knocked out when the food was about ready and one thing and another and

then they tried issuing us with our food and saying, “Well now, everyone light a

little fire all the way along the trench and the Germans won’t know which to shell,

you see, and they won’t shell at all”. The

trouble was there that we got lazy and nobody would cook and we used to eat the meat raw

and so we got sick, it didn’t agree, so they went back to this other and take their

chances. Of course, when they really knocked

us out, we’d have to eat bully beef and biscuits which was cold but it was good food. We had lots of cheese, more cheese than we wanted,

but that’s all we had that winter was bully beef, biscuits and cheese and jam. That’s what we live on.

|

|

Q

|

Do you remember that

dugout, was it as big as this studio?

|

|

A

|

Oh no, we crawled in,

you know. It would be about six by six.

|

|

Q

|

For three men?

|

|

A

|

For three men, yes

|

|

Q

|

How high, could you

stand up in there?

|

|

A

|

No, you’d go in on

your haunches, crawl in. It would be about

four or five feet high perhaps. It all

depended, of course, on how big the parapet was. It

was there and the parapet was in front and then the ledge was up above. The man who was on duty stood on the ledge and he

could see over.

|

|

Q

|

Did you have any kind

of bed in there or was it earth?

|

|

A

|

No, it was dirt. We had our blankets of course. We were quite used to it. I don’t remember not sleeping.

|

|

Q

|

You would be able to

Keep a small place like that quite warm?

|

|

A

|

Oh yes, we had little

braziers, you know. We had coke and we’d

light the brazier outside and leave it there until the gas got burned off it and then take

it in and that would warm it up and then we’d have to put it outside shortly

afterwards. We used to make toast on those

things, you know. They issued one loaf of

bread per day to each three, you see, and a can of bully.

We very seldom got any butter. We used

to get a can of jam.

|

|

Q

|

What about water, that

must have been a problem.

|

|

A

|

It came up in tins, you

know, gas, I think about a gallon.

|

|

Q

|

Some say they’re

two, I’m not sure.

|

|

A

|

They came up in that

but the water wasn’t too good, you, know, because they had it all doctored up for us

to keep our vitalities down and one thing and another.

|

|

Q

|

Were you able to keep

clean?

|

|

A

|

No, lousy as pet coons. When we went out, of course, we’d do a week,

ten days or two weeks in and then go out for a few days and we’d go back about three

miles. Right there we went to la Clytte and

they had a lot of women with tubs, you know, and we’d be on one side of the blankets

that were held up as a shield with a tub of water. At

one place they had a little kind of a shower or pipe dripping some water. We’d get undressed and throw our clothes over

to the women and they’d start washing them and then the sergeant would holler about

the water coming on and he’d turn it on for a minute and turn it off and then

we’d soap and he’d turn it on again for a minute and we were supposed to have it

washed off. Then we’d put on the

supposed to be clean underwear but ten minutes after you had it on you could feel the

cooties just as bad as ever. A little later

they got steam baths that they used to put them in and I think that got rid of them but I

don’t…….

|

|

|

At this point there is a page missing from the transcript

|

|

Q

|

In the spring though it

seems to me there was always plans for a spring offensive. How did you fit into all that, did you find

your unit called upon?

|

|

A

|

No, we had Messines. They told us that they were going to have an

operation at Messines, going to blow it up, but they did that in the fall. When we first went to the M and N they did that

and they ordered us to rapid fire at a time at a certain time, all along the line, you

see, and we were five, six, seven miles away from Messines but we rapid fired just to

train and bring the fire away from Messines but, as I say, fifteen minutes afterwards we

didn’t have a gun that would fire. You

see, the Ross got heated up and get plugged up. Of

course, eventually, we only had them while I was there.

Just after I left they started to issue Lee Enfields.

|

|

Q

|

During all this time

there was some mining?

|

|

A

|

We were doing mining,

at least the mining company were doing that. We

had to supply so many fatigue men each night and they were undermining a hill just to the

left of us. They got that all set without any

trouble you know. We used to detect mines

that the Germans were putting down and they would do ours and blow them if they could but

they didn’t these. In March we blew this

hill sky high and made about three big craters.

|

|

Q

|

St Eloi?

|

|

A

|

St Eloi. We went and occupied the craters, we had to

fight for them, and then the next night they took them back again and we took them back

again. Finally after about two weeks there

were no craters, it was all flat. They’d

just blown the whole thing flat again so we didn’t really gain anything.

|

|

Q

|

But the hill was a

little lower, I guess.

|

|

A

|

Yes, they couldn’t

put snipers in there. It was on their side

too so we picked up perhaps a hundred yards, that’s about all.

|

|

Q

|

This kind of a skirmish

attack must be a tricky thing to fight over.

|

|

A

|

It was very tough, very

tough. You know, I always believe that the

only reason that you get the other guy was because he was going to get you. I don’t really think that we hated people

enough to want to go out and kill them, you know.

I think we only had one or two fellows, we had a couple of Indians with us,

snipers, and they loved knocking fellows off who were walking along but I don’t think

any of the other fellows would.

|

|

Q

|

It’s a special

kind of mind.

|

|

A

|

Yes. They didn’t seem to mind doing it at all.

|

|

Q

|

What about scouting, I

would like to know in a general way what that’s all about.

|

|

A

|

We had to know maps and

how to read maps, that was about all, and moving about of course. We crawled and then they took away our rifles and

gave us bombs and revolvers. We got an issue

of revolvers then and we carried two Mills bombs with us as soon as they came out. Of course, we didn’t have those to start with

but they came along.

|

|

Q

|

Can you tell us,

what’s a Mills bomb like

|

|

A

|

A Mills bomb is the one

very much like a lemon and it was built square like that, square iron, and it had its

handle on it and the pin. You pulled the pin

and held it but if you let it go then it would go off and so and so, you see, but it was

just a nice thing that you could bowl out and you could bowl it quite a distance, bowl it

a hundred feet very easily. Some of the boys

could throw it far more but even I could bowl it that far.

They were handy, you could toss them into a crowd and our job was to patrol the

space between our trench and the German trench and, of course, we used to run into their

patrols doing the same thing and we’d watch, you see.

Of course, we always had our password to get back into our line. We used to go out and be out there nearly every

night. Somebody would be out there and

we’d just wander up and down, either crawl or walk, it all depended on how much rum

we’d had before we went out whether we walked or crawled sometimes but I always

figured that that was the safest spot to be because they never shelled in No Man’s

Land on purpose. Their shells would all go to

the trenches or behind them. I did that

all winter.

|

|

Q

|

Do you have any

adventures that you recall?

|

|

A

|

Well, we ran into

Germans two or three times. One time we had

to go over and count the number o sandbags in the front line, German’s line, which we

did and we thought that was going to be a terrible job but the only bad part of if was

getting through the wire.

|

|

Q

|

What would the purpose

of going over?

|

|

A

|

I think they wanted to

know how much strength they had, I think, by how much they needed to shell or what kind of

shells they needed to knock it down. It’s

hard to realize, you know, some fellow would say back in the artillery “Perhaps we

should put a five inch in there or a whizbang might do it and there’s no use wasting

anything if we can find out”.

|

|

Q

|

What about this wire,

was it a pretty complicated wire, I’ve seen some modern wires, was this just the

same?

|

|

A

|

About the same. We used to string it up. It was done with posts like this. The wiring parties went out and they’d hammer

in the posts and then put the wire down any way they could as long as it was attached

there. It was pretty hard to blow that stuff

around you know, with shells.

|

|

Q

|

How would you get

through it?

|

|

A

|

We used to cut it and

we used to have little holes, you see. We

knew where we were going and we’d cut a hole down underneath, hoping that the Germans

wouldn’t find the same hole, of course, then we’d have to go over and cut theirs

the same way in order to get in between theirs and dodge flares but sometimes you’d

have to knock a guy on the head that was on the parapet and, if you could do that quietly

without anybody bothering and nobody came along, you could count the number of bags

alright. Anyway, we did gather information

for them.

|

|

Q

|

I’ve often heard

people talk about listening posts. I suppose

this would be part of your duties?

|

|

A

|

I wasn’t a scout. We used to have listening posts and they were

manned by the fellows in the actual trench. They’d

have two hours on and then they’d come in and perhaps be posted for the night so

they’d have four hours off and then two hours on.

They actually had three fellows out there and that was a little trench they ran out

from our front line, they run it out twenty or thirty feet and then put a little round

place and they’d just sit out there.

|

|

Q

|

What would they hear?

|

|

A

|

They’d know first

about an attack, you see, because they had a connection from there back to the trench and

if they heard anything at all they’d warn the trench that they were coming because

they were out of luck usually because the Germans usually got them.

|

|

Q

|

You were saying that

the scouts out there in no man’s land were pretty safe but surely you know

that’s an exaggeration?

|

|

A

|

We always figured that

it was safe from gun shell anyway. I suppose

no place was safe

|

|

Q

|

Surely you could be

seen. There were shells.

|

|

A

|

They didn’t put

those up all the time, you know.

|

|

Q

|

I suppose, if they did,

you’d just duck?

|

|

A

|

Oh yes. If they heard anything, up would go a shell or

our fellows would put it up when we didn’t want them to sometimes but we were there

about a hundred and fifty to a hundred and seventy yards away from the German front line

and it was more or less straight land. We

were just out there.

|

|

Q

|

Did you ever bring in

some prisoners when you were scouting?

|

|

A

|

Yes, we did that too. In fact we made a little raid one night.

|

|

Q

|

Tell us about that.

|

|

A

|

Well, we were asked if

we could get hold of a prisoner. They did the

same thing to us.

|

|

Q

|

Now many would there be

with you in this raid?

|

|

A

|

I remember it was six

once but we usually carried about ten and we wouldn’t all get there either because

they’d usually, the fellows in a bay would hear us.

All we had to do was get one fellow because they’d have to dispose of the

other two, you know, or something like that, usually two or three. They’d go down into the bay too, some of

them.

|

|

Q

|

Into the German trench?

|

|

A

|

Yes, into the German

trench. We’d have our bayonets like the

ordinary fellows, we’d have the bayonets and then we’d have our revolvers. They were very handy, the revolvers. I had a knife, a dagger. It had a knuckle duster here and then a dagger

like that. My uncle gave it to me in England. He was a Colonel.

I took that with me and that was very handy. The

fellows would run a mile if they saw that.

|

|

Q

|

A good strong tool for

hitting too?

|

|

A

|

Oh yes. We did that several times. That would give us, we’d get the man, and

that would tell us what regiment it was that was there and some of the regiments were far

nicer and far easier than the others. If we

got the Saxon fellows, there was never any trouble, but if we got the Prussians, we were

up against it and we knew it.

|

|

Q

|

Well, this is most

interesting and I can see you in a nice spring night squatting out there with a group of

six or eight and doing some quiet little raid on the side. Now, after the Craters at St Eloi, what

happened to the battalion then?

|

|

A

|

Finally they just built

a new trench, you know, I was on that party too.

|

|

Q

|

It seems to me more of

you people just worked.

|

|

A

|

Oh yes. We went up and we had to dig six feet long, two

feet wide going down to a foot at the bottom and six foot deep and, when you dug that, you

could go home. We usually, two of us would

get together to do the double, the twelve foot because we could work together, one

shoveling and the other the pick. We

didn’t do that with regular shovels and picks, you know. Half the time we had to do it with our trench

tools.

|

|

Q

|

What were they like?

|

|

A

|

They were a one-sided

pick with a handle about so far.

|

|

Q

|

How long would that be?

|

|

A

|

A foot and a half. I don’t know whether they were quite that

long because we carried them in our belts, a shovel in one and a pick at the other end. We’d pick a bit and then shovel but we could

do that in about three hours, we could dig our piece.

Mind you, of course shells were coming at you all the time so you dug a lot faster,

especially to get down, you see. If you could

get a hill in front of you, well then he kind of eased off a bit. While there was any chance of getting hit, you

really dug and then we went home for the night. They

just go home. We’d march up there but

when a few of us would get through we’d go.

|

|

Q

|

You finished your

piece.

|

|

A

|

Then the other fellows,

you see, in the daytime would come along and lay the duck and fix the trench up and finish

it off and that kind of thing. It was just

getting the main job done at night. I

didn’t do too much of that but I did enough to know about it. Of course, you see, if anybody got into any

trouble, if any of the fellows were crimed or anything else, that was the job they got. They had to do that or they had to do the wiring. We had an experience with one fellow, he was a

real tough egg, he was always in trouble. He

couldn’t do anything but fight. He’d

get fighting, anything to get into trouble. He

was court martialed once for stealing our rum. It

was only one jar of rum but it meant an awful lot of fellows didn’t have rum you

know. Mind you, we hated him for it then but

since we joke about it. It comes up at every

reunion.

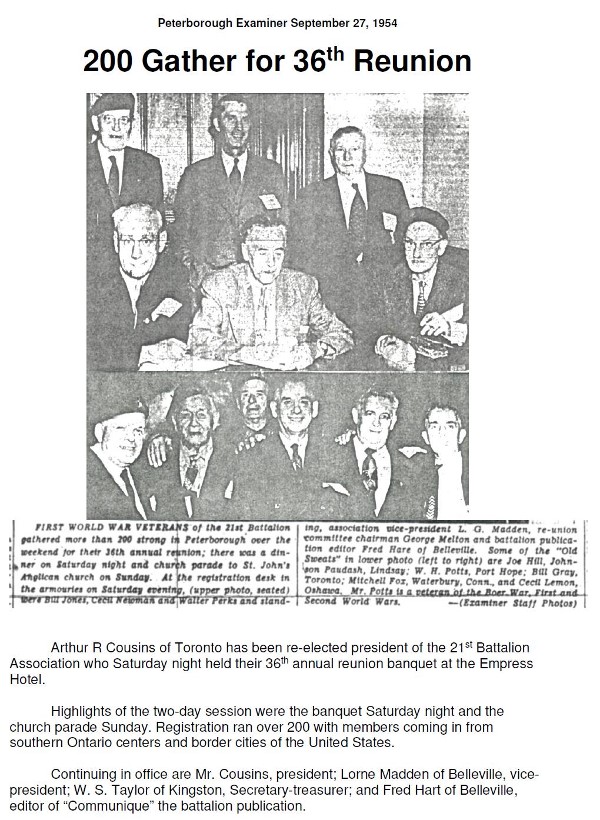

A.R. Cousins 59207, Tape #2

|