|

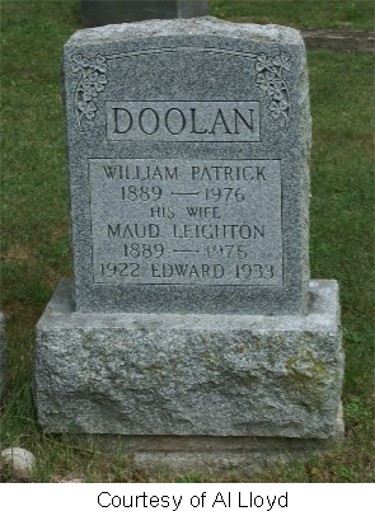

William Patrick Doolan, MM

|

|

The Kingston Whig

Standard November 12, 1988 A LOCAL HISTORY IS A complicated -- if very

satisfying -- exercise in research and writing, but it has to exist at several different

experiential planes if it is to succeed. At one level, the "local" experience

fits into the regional, the national and the international as part of the broader

economic, social and political picture. At another level, "local" history must

also develop the distinctiveness of particular places. But if the writing of "local" history is

to truly capture the essence of place, it must also incorporate the people -- all of them.

We cannot write of Kingston's early years without referring to John Ross, Michael Grass

and Molly Brant; but what about the Mississauga chief, Mynas, who sold his lands to the

Loyalists? The Cartwrights and Stuarts were prominent members of Kingston's nascent

society, but so in their way were local worthies such as Bridget McDallogh who ran off

with Tim Ghigan, "the lame fiddler ... that was put in the stocks last Easter, for

stealing Barney Doody's game cock." Indeed, local history requires that writers

transcend the usual subject-object relationship of traditional scholarship. In writing a

community's history, the writer and the subjects are fused together in a joint enterprise

of reconstructing the lived-in-past. All these elements come into play when trying to

understand the impact of the First World War -- the Great War on the local community:

Kingston's part in an international conflict; Kingston's distinctive military tradition

and role; and the impact of the war on the local citizenry. Much of this is accessible in

standard archival and library sources, but the more personal experience of the

citizen-soldier is usually quite elusive. Luckily, however, we had a little treasure trove

of memorabilia to help us. Plumbing repairs in an attic in a house on

Macdonnell Street yielded dozens of postcards, several unlabeled photographs, "Khaki

Club" library books, and a few military documents. From these -- together with the

official records of Regimental No. 454549 -- we outlined the enigmatic odyssey of one

William Patrick Doolan, a Kingstonian who volunteered to serve overseas in the First World

War. Some of this was used in Kingston: Building on the

Past as a vignette of a citizen-soldier's war. This stimulated involvement by local

readers: Doug and Willa Thompson provided a family picture of three generations of Doolans

and a contact with "Paddy" Doolan's surviving daughter, Mary Mellow; Mrs. Mellow

has filled in some of the gaps in the family story by identifying photographs and

recalling her father's reminiscences; a colleague at Queen's, Ken Russell, reported on

Paddy Doolan's decades of service as a technician and character in the department of

chemistry at the university; military records provided details of Paddy's military career. With these reactions, our partial vignette was

being fleshed out into a family and social context. William Patrick Doolan's war -- Paddy

Doolan's war -- started to come alive not only as a military experience but as part of the

family's experience during these harrowing days of The Great War. Sgt.

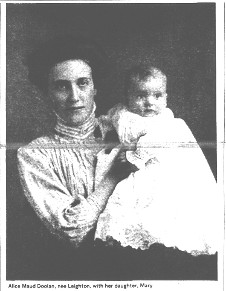

Doolan of the 21st In August 1914 William Patrick Doolan,

"tanner," was living at 13 Clergy St. West with his wife Alice, the former Alice

Maud Leighton. Like many Canadians of the day, he was an immigrant, having been born in

Birmingham, England, on Dec. 22, 1889, to a large Irish family. Like other Kingstonians,

he could not fail to be aware of the onset of war and of Canada's role in it -- especially

as a member of the local militia. Indeed, his was a military family: his father,

father-in-law, brother and brother-in-law would all soon be in uniform. International tensions increased throughout the

summer of 1914, and with the inevitability of British involvement, crowds assembled around

the Daily British Whig's Bulletin Board. On Aug. 4, the Whig reported: " Kingston has

been stirred by the war. News from the front has been eagerly sought. Everybody is talking

war. On the streets, in the offices, in the shops, in the stores .... The seriousness of

the situation has been realized." The next day, the headlines declared the expected:

"All Europe Aflame in Mighty Struggle." Subsequent editions affirmed that

Kingston had "war fever," but apart from a few fist fights between local

patriots and a few unfortunate "saurkraut-eaters," Kingston was spared the

excesses of patriotic fervor that saw burnings and affrays elsewhere throughout Canada. The local military moved quickly to the qui-vivre:

British officers at RMC returned to Britain to join the colors; the RCHA batteries were

placed on alert; men of the 14th Regiment guarded such vital facilities as the Cataraqui

Bridge, the ammunition depot at Fort Henry, the Barriefield wireless station, Kingston

dry-docks and the water supply. Such was the concern that the local populace was warned,

"The 14th men are on real war duty, and they have orders to fire on anyone prowling

about guarded territory and refusing to make known their business." But apart from

reports of a mysterious plane landing and taking off near Barriefield, the accidental

discharge of a rifle and feared threats to the grain elevators, there were few real

disruptions of the local peace. There was no doubt, however, that a state of war

existed in Canada as well as in Great Britain. And certainly local military preparations

underscored this. Kingston was the home-base of the local militia unit, the 14th Princess

of Wales Own Rifles. Its facilities and military heritage required a more substantial

role, however, and on Oct. 19, 1914, Lt.-Col. (later Brig.-Gen.) William St. Pierre Hughes

was authorized to organize the 21st Battalion of infantry to be drawn from the eastern

Ontario region. Recruits were billeted at the Armouries, the stables of the Royal Canadian

Horse Artillery, the adjacent Artillery Park and a cereal mill at the foot of Gore Street. The battalion trained for the next six months, and

on May 5, 1915, it received its own colors from the Kingston's Army and Navy Veteran's

Association. The Daily British Whig reported that 15,000 people lined Montreal Street to

the Grand Trunk Junction Station. As the bands of the RCHA, the 14th and 21st, played The

Girl I Left Behind Me, Tipperary and Johnny Canuck's The Boy, the trains rolled out from

Kingston en route to Montreal. The next day the battalion boarded the Metagama together

with hospital units from Queen's, McGill and Laval universities and, by May 16, was

encamped at West Sandling Camp, Kent, as a unit of the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 2nd

Canadian Division. On Sept. 14 of that year it received the order to embark for France. Paddy Doolan did not leave with the 21st in May

1915. He had enlisted with the 14th Princess of Wales Own Rifles militia in 1899 while

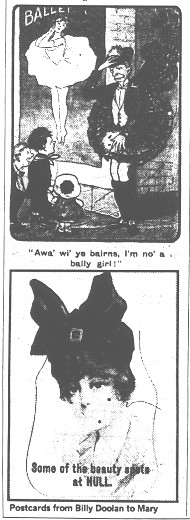

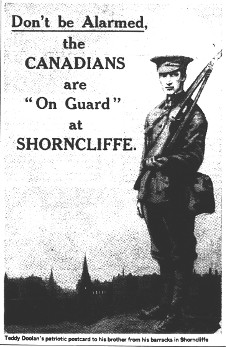

continuing to hold down his job in the tannery. His brother, Teddy, had already gone

overseas, however, and sent a patriotic postcard from his barracks at Shorncliffe saying,

"It won't be long before you will be here for they want more." Teddy also

enquired after the "baby." The baby was Mary Doolan, born on Oct 22, 1914. It

was Mary who was to receive the dozens of postcards that documented Paddy's experiences in

the Great War. On July 3, 1915, Paddy Doolan signed his

"attestation paper" for service with the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force.

He gave his permission to be vaccinated, affirmed that he understood the nature and terms

of his enlistment and made this formal declaration: I, William P. Doolan, do solemnly declare that the

above answers made by me to the above questions are true, and that I am willing to fulfill

the engagements by me now made, and I hereby engage and agree to serve in the Canadian

Over-Seas Expeditionary Force, and to be attached to any arm of the service therein, for

the term of one year, or during the war now existing between Great Britain and Germany

should that war last longer than one year, and for six months after the termination of

that war provided His Majesty should so long require my services, or until legally

discharged. This was followed by a formal oath: I, William P. Doolan, do make Oath, that I will be

faithful and bear true Allegiance to His Majesty King George the Fifth, his Heirs and

Successors, and that I will as in duty bound honestly and faithfully defend His Majesty,

His Heirs and Successors, and of all the Generals and officers set over me. So help me

God. Three days later, the completed attestation, declaration and oath were certified by

the magistrate and approving officer, and Paddy Doolan joined the Canadian Over-Seas

Expeditionary Force. Following his enlistment in the 59th Battalion,

Paddy Doolan was part of the recruitment effort that saw units of the local troops touring

Kingston's back-country, visiting farms and enticing young men to volunteer for services

overseas -- a duty that did not make him a welcome visitor to the farmsteads of the area.

But by April 11, 1916, he had arrived in England and sent a postcard from Liverpool with

this assurance to his wife: "Arrived safely. Cannot cable. Don't know where we are

going." Like many other members of the CEF he was

stationed at Shorncliffe, where he received instructions in entrenching before proceeding

to an NCOs course. On July 11, 1916, he was taken on the strength of the 39th at West

Sandling with the rank of sergeant. A month later, at his own request, Paddy Doolan

reverted to the permanent rank of private and proceeded overseas to reinforce the 21st

Battalion. On August 31 he joined the ranks of his home-town battalion. With

the 21st in Action By the close of the war, the 21st's colors were to

include battle honors for St. Eloi (1916), Somme (1916), Vimy (1917), Hill 70 (1917),

Passchendaele (1917), Amiens (1918), Arras (1918), Cambrai (1918) and Mons (1918) -- and

Paddy Doolan was to share in several of these engagements.

Within three weeks of joining his unit, Paddy was

a casualty. On Sept. 30, 1916, Lance-Corp. Doolan had received several gunshot wounds.

Apparently, these were not serious -- if ever gunshot wounds are not serious -- as

following a brief stay at the Divisional Rest Station at Warloy, he was discharged back to

duty on Oct. 7, 1916. Not until Dec. 4 of that year did the Department of Militia and

Defence notify his wife, Alice Doolan, of his condition with a terse I have the honor to state that information has

been received by mail, from England, to the effect that the marginally noted non-

commissioned officer was transferred from the Divisional Rest Station to No. 4 Canadian

Field Ambulance on October 4, 1916, suffering from gunshot wounds in the hip, shoulder and

face. But by that time, Mrs. Doolan was no longer in Canada. Life with a young baby and no

bread-winner must have been hard in 1916, and she risked the hazards of an Atlantic

crossing to be closer to her husband. Together with her young daughter, Mary, she stayed

with relatives at Weymouth, and it was here that she received the limited news provided by

a multiple-choice Field Service Card: "I am quite well.... I have received your

letter. Letter follows at first opportunity." January and February 1917 saw Paddy Doolan at a

"bayonet fencing course," and on April 12, 1917, Corp. Doolan was again promoted

to the rank of sergeant. On Oct. 31 he was granted 10 days leave, rejoining his unit in

the field on Nov. 17 -- clearly, arithmetic was not his forte! Christmas was spent in

France, and a program for the dinner for the sergeants of the 21st Canadian Battalion

established the order of proceedings and the tone of the event: party-goers were warned

that there would be "only one fight for each W.O. and Sergt.," that there would

be "no issue of whale oil" and that "Stretcher Bearers" would be in

attendance. An imaginary orchestra was to play "She sits among the cabbages and

peas" and the various other performances included a "Song (If Sober) from Sgt.

W.P. Doolan." Two days later, Sgt. Doolan was ordered to proceed

to England for a musketry course at Hayling Island. He returned on Feb. 4, 1918, with the

commendation that he was "fit for musketry instructor." He was soon back in

action, and a citation dated March 15, 1918, described the events for which he was

recommended for a Military Medal:

“For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to

duty. In connection with a raid on the enemy trenches, this Sgt. showed great initiative

and daring in house to house fighting. He led his section with great determination against

an occupied house, and owing to his gallantry and personal braveness sic, succeeded in

occupying it. He personally killed several

of the enemy, thus allowing the second party to advance. It was largely owing to his

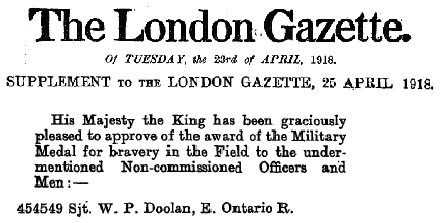

gallant action that the raid was a great success.” The award was reported in the London Gazette on

April 25, 1918, but on May 12 Sgt. Doolan was wounded again -- this time, a shrapnel wound

to the head, which he described as a real "blighty," and he was invalided back

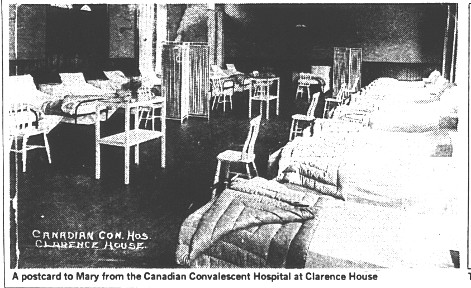

to Britain. A flood of postcards to his daughter, Mary, marked his movement from hospital

to hospital -- the Canadian Convalescent Hospital at Clarence House in July, the 4th

Canadian General Hospital Basingstoke in October. But all of this had been interrupted by

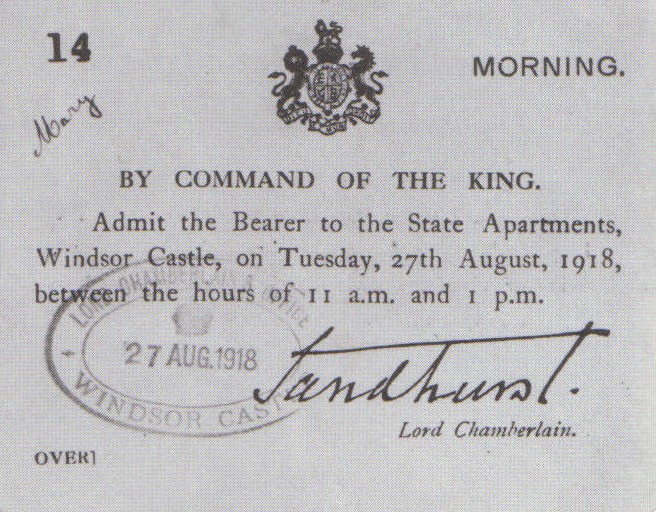

a major event. On Aug. 27, 1918, Sgt. W.P. Doolan received a formal invitation from

Sandhurst, the Lord Chamberlain, "By Command of the King," to "Admit the

Bearer to the State Apartments, Windsor Castle, on Tuesday, 27th August, 1918, between the

hours of 11 a.m. and 1 p.m."

In Kingston, Alice and Mary had returned from

overseas. They were much involved in helping the grandparents-Leighton run the Khaki Club

in buildings behind the Fire hall on Ontario Street. Soldiers and sailors dropped in for

drinks, sandwiches and books while on leave or recuperating from their wounds. The war was

to drag on for months yet, but on Monday, Nov. 11, 1918, the first Kingstonian to hear of

the Armistice was Columbus Hanley, manager of the Great North Western Telegraphy Company,

when at 5:00 a.m. he received the message, "The Armistice is signed." Bells and

sirens proclaimed the news, and by 6:30 a.m. the Market Square was full of celebrating

inhabitants, students and returned soldiers. The Daily British Whig's banner headlines

proclaimed, "The War Is Ended, Kaiser Abdicates, Germany Quits, It's Over -- Over

There." Mayor Hughes cabled King George, "Kingston enthusiastic in

demonstration. We send loyal greetings and pray God Save the King." Nor was President

Wilson neglected. Hughes cabled, "Heartiest greetings and fondest felicitations.

Proud of your country's part in bringing about victory. May we long abide together in

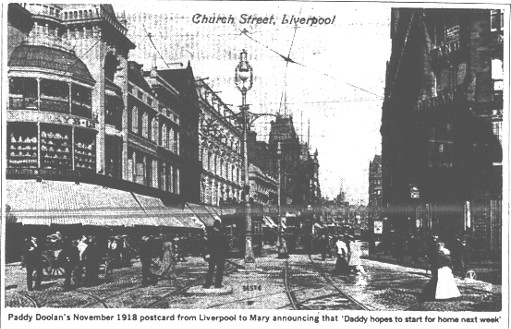

unity." Back in Britain, Sgt. Doolan cooled his heels in

Liverpool. He had been notified that he was to be invalided to Canada. Throughout November

his daughter received a barrage of postcards letting her know that her father was

"fed up with waiting." But on Nov.22 came the message, "Daddy hopes to

start for home next week." By Friday, Dec. 20, 1918, he had arrived in Halifax and

wrote, "Arrived O.K. Expect to start for Kingston tomorrow (Saturday), and get home

Monday." At 4 p.m. on Sunday, Dec. 22, a large crowd assembled at the Grand Trunk

Station on Montreal Street to meet a hospital train carrying four officers and 37 NCOs on

their way to the Queen's University Military Hospital. The Daily British Whig reported the

event: The mayor welcomed the boys on behalf of the city,

and spoke of the gratitude of the people of Canada to those who had fought and suffered in

order that the war might be won. He assured them that the city of Kingston was proud of

the part they had played, and that the people were willing and ready to do all in their

power for them in every way. Three Kingstonians were among this contingent, including Sgt.

W.P. Doolan. On Feb. 21, 1919, Paddy Doolan -- holder of the Military Medal, British War

Medal and Victory Medal -- received an honorable discharge, "being medically unfit

for further War Service." "Lest We Forget" But this did not end

the war for him entirely. Like many of his fellow soldiers, Paddy Doolan never forgot the

horror, filth and deprivation of the trenches. Nor did he forget his comrades who had

fallen. Together with other veterans, W.P. Doolan was a member of the "Memorial

Committee" chaired by A.T. Tugwood that sought to establish a permanent tribute to

the men of the 21st who had fallen in the Great War. There had been some recognition. On Dec. 12, 1921,

the King's colors of the 21st were placed in St. George's Cathedral. Three days later

Baron Byng of Vimy, the former commander of the Canadian Corps and then Governor-General

of Canada officiated at the unveiling of the Memorial Tablets and the dedication of

Memorial Hall at City Hall. Stained-glass windows commemorated the 254 Kingstonians who

had fallen in several theatres of the war: Ypres, April 1915; St. Eloi, April 1916; Somme,

1916; Jutland, May 1916; Sanctuary Wood, 1916; Lens, August 1917; Vimy, April 1917;

Passchendale, 1917; Cambrai, 1918; Amiens, August 1918; Scapa Flow, November 1918; Mons,

November 1918. But the 21st merited individual recognition. Mary

Doolan remembers pouring over a book of designs with her father and selecting the one that

was dedicated on Nov. 11, 1931. On that day, City Park was the scene of an elaborate

program of events to mark the unveiling of the War Memorial for the 21st Canadian Infantry

Battalion, CEF. Pride of place was given to the parents of soldiers killed in action --

especially those of Cecil Boyer of Belleville, the first of the 21st to fall at Messine

Ridge. While the military units present stood to attention, the flags veiling the memorial

were released by mothers of sons killed while serving with the 21st. Maj. Rev. W.E. Kidd,

MC, padre of the 21st, dedicated the memorial to the Glory of God and in the name of

fallen comrades, closing with a plea for peace and understanding between the nations of

the world. The dedicatory address was given by Lt.-Col. J.C. Stewart, DSO, officer

commanding the RCHA. He paid tribute to the regiment and the fallen: The history of the 21st Battalion is the history

of the Canadian Corps, and is inscribed as one of the most precious pages in Canada's

history. The position of Canada today in world affairs is very largely due to the name

made for Canada by her soldiers in the World War. It is a position for which the 21st

Battalion can justly claim her due share. The pipe band of the PWOR -- the regiment

perpetuating the 21st Battalion -- played Flowers Of The Forest, and the Last Post and

Reveille were sounded by former buglers from the 21st Battalion. Appropriately, at the banquet held that night at

the La Salle Hotel, the toast to "Canada and the British Empire" was proposed by

one of Kingston's heroes, Brig.-Gen. A.E. Ross, CMG, MP; the toast to "Our

Guests" was proposed by another, William P. Doolan, MM, Esq. Paddy Doolan died on March 11, 1976, but he never

forgot his service overseas some 60 years earlier. Nor would his daughter, Mary, and wife,

Alice Maud, who also shared his fears and their own suffering and deprivation during the

Great War.

And for years after the Great War, Mary polished

his medals for the Friday evening drills with the PWOR, where he continued to serve as

sergeant. During these years, while he trained new recruits to his old unit, he was

carving out a new career. For some four decades -- after years of independent study -- he

served as a much-valued and highly respected technician in the department of chemistry at

Queen's. He was sorely missed by faculty and students alike on his retirement. And in 1988

his granddaughter, Kathy Mellow, graduated from Queen's with a B.Sc. Eng. before returning

to her unit at Camp Borden as lieutenant in the Canadian Army. A Queen's graduate and an

officer too. Paddy must be very proud! |

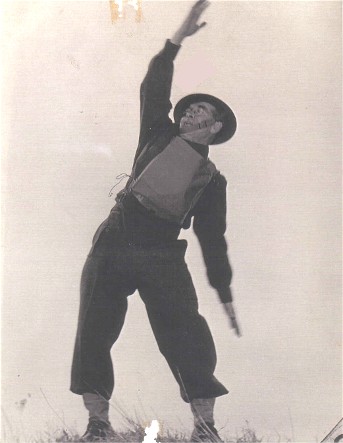

| Below, Paddy is shown

training troops of the 14th PWOR at Kingston for possible action in WW2

|

|

|

|

Paddy Doolan's medals |