|

Walter Tait Govan A Vanguard's Medal Michel Gravel I made the acquaintance of the late Lt. Walter

Tait Govan in 1995, just after my family had set up house in an old and modest home on the

bank of the Raisin River, in the heart of the Loyalist hamlet of Williamstown, Ontario.

Our dwelling was well known to the locals by an equally old and modest name: “the

Hired Man’s House”. As this name implies, this rustic 1840’s vintage home

was a secondary dwelling on a larger property. The main house, (today known as the

Bethune-Thompson House) located across a private lane we shared, was begun in 1784. It has

the reputation of being Ontario’s oldest residential building. This pioneer cabin,

later enlarged, had, as one of its first occupants, the Reverend John Bethune. The reverend Bethune, a Loyalist, became the

founding Pastor of the newly formed Presbyterian congregation of St-Andrews (1787) in the

new settlement of Williamstown. His home, by default, became the first Manse. The congregation’s present church, not far

from the Manse, was built in 1812, making it one of the oldest churches in Ontario. (Since

1925 it is part of the United Church of Canada) This venerable building and its lovely

setting attracted me from the beginning. The setting is serene: The church is nestled

among trees at the end of a lane and surrounded by the congregation’s cemetery. An

ancient wrought iron fence, venerable and in need of a bit of repair, stands guard over

they who are at rest. Many times I took walks to visit the churchyard,

as I have always been attracted to cemeteries. My interest for these places is not morbid

or occult in nature, rather, it is for the historic and journalistic opportunities they

offer. A cemetery, even a small one, contains a large compendium of stories that, apart

from the usual obituary, have never been investigated. I remember the first time I passed through the

gates and entered the churchyard: an inscription on a plaque confronted me: “Tread softly, stranger, reverently draw near, the vanguard of a nation slumbers here.” I immediately appreciated my status as a

“stranger” and complied with the inscription. I proceeded into the burial ground

as quietly as possible. My curiosity was rewarded with many early headstones marking the

resting place of local pioneers. I was conscious of my behaviour and endeavored to

continue my visit in silence, lest I trouble the sleep of the interred. I didn’t know

what Highland wrath I could unleash on myself if my “treading” became too

clumsy. My perusal of the markers and crosses revealed an interesting fact: some of those

commemorated in marble I could not disturb even if I tried, as they are resting in

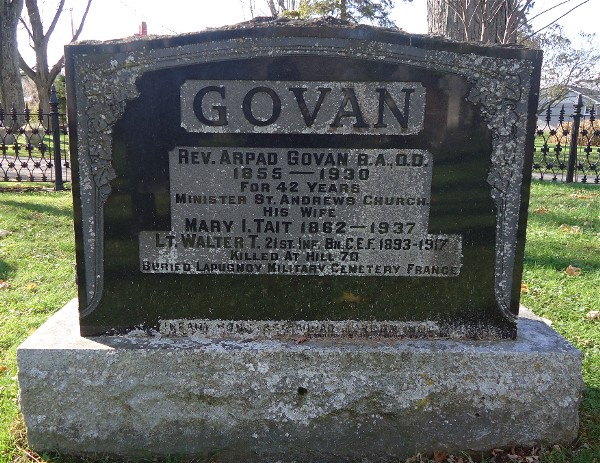

far-away France. They are the congregation’s soldier-citizens of the two Great Wars. In front of the church, I noticed the headstone of

the Govan family. One of the family was an officer of the Canadian Expeditionary Force: Lt

Walter Tait Govan. His father, the reverend Arpad Govan, who died in 1930, was a successor

of Bethune, as he was the Pastor of St-Andrews at the time the Great War. Many times I

visited the Govan family plot after this episode. The following year I left Williamstown for

Cornwall, my hometown, a city 20 minutes distant. My visits to St-Andrews churchyard

became much less frequent. I believed my connection to it was at an end. I did not know

it, but I was destined, in a few years, to cross paths again with Lt. Govan. In 2001, I began research into the military career

of an ancestor who was drafted into the Canadian Expeditionary force in 1918. This

rekindled interest in the Great War led me to peruse many sources of research material

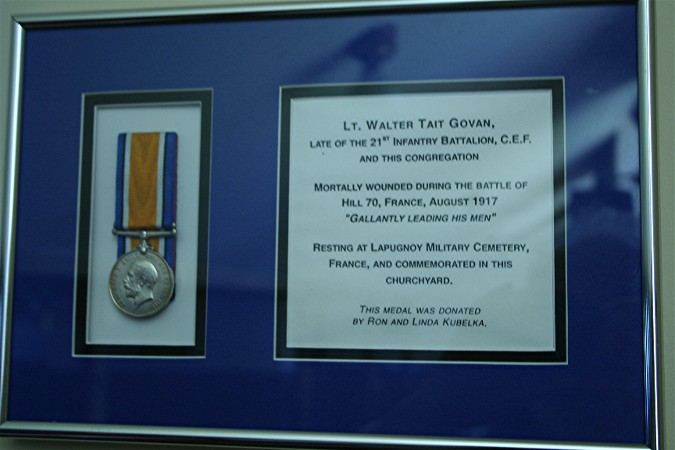

including the Internet. It was on a militaria dealer’s site in Kingston, in 2002,

that I found for sale, a World War 1 silver British War Medal, inscribed to a Lt. W. Govan

of the 21st battalion! I was understandably excited to have found one of the service

medals awarded to my Lt. Govan, whose path I had crossed seven years prior! (The British

War Medal was awarded to British Empire soldiers who served overseas during the Great War

of 1914-1918. Govan’s other medal, the “Victory Medal” is still missing.) An inquiry directed to the vendor confirmed that

the “relic” was indeed still for sale. It had come from a recently divested

private collection. I immediately contacted Mr. Ron Kubelka, a family friend and member of

the St-Andrews congregation and informed him of my find. He immediately, and generously

offered to acquire the medal and donate it to his congregation. I was informed that the medal was to be dedicated during the Remembrance Day service (November 9, 2003) of St-Andrews, Williamstown. It was to be put on permanent display in the church.

Upon hearing this news, I felt compelled to look

into the details of Lt. Govan’s war service. Govan arrived at the front in June of 1917, and

was posted to “C” company, 21st Canadian infantry battalion. By the end of July 1917 Sir Douglas Haig, the

Commander of the British Expeditionary

Force, launched his second major offensive of 1917. (The first involved a spring offensive

centred on the ancient city of Arras, France, and included the capture of Vimy Ridge.)

This new effort involved the “breakout” of the British army from the infamous

Ypres Salient in Flanders, with a view to capturing the Belgian channel ports; which were

in German Hands since 1914. Sir Arthur Currie, of British Columbia, the

Canadian Corps’ new commander was assigned the task of attacking the mining city of

Lens, situated near Vimy Ridge, in support of the British Flanders offensive. The

objective was to “tie-down” German Divisions in this sector of the front, and

thus prevent their relocation from France to Belgium. Currie, the greatest military leader ever produced

by Canada was not satisfied. He modified the plan: Instead of attacking Lens and its ruins

directly, Currie opted for an indirect approach to reaching Haig’s goal. He would

avoid Lens proper, and instead, he would capture the dominating high ground known as Hill

70, located North-West of the city, After a postponement, Currie’s battle of Hill

70 (his first major offensive as Corps Commander) was launched in the early morning of

August 15th, 1917. The 21st battalion (recruited from Eastern Ontario) was one of the

units assigned to the initial assault, just south of Hill 70. “C” company of the 21st Battalion was

led by a group of four officers. Three were militiamen: Lt. Belmont Lloyd Irwin, of

Cornwall and Walter Tait Govan of Williamstown, both served with the defunct 154th

overseas battalion, C.E.F. The third militiaman was Lt. Grant Davidson Mowat, of

Peterborough. The 154th battalion was the overseas contingent of

the 59th regiment of militia, which is perpetuated by the Stormont Dundas & Glengarry

(SD& G) Highlanders. Unfortunately, like many battalions, the 154th was “broken

up” in England, before it could see service at the front as a unit. The soldiers were

used as reinforcements and thus served their country with other infantry units already at

the front. This said, enough men of the old 154th served at Hill 70 that the defunct

battalion was awarded the battle honour Hill 70. Today, this battle honour is perpetuated

by the SD & G Highlanders. Mowat and Irving had accepted demotions to proceed

on to France. The fourth officer, Lt. Arthur Edmond Jones, MM,

was the decorated veteran of the foursome. He was an original member of the 21st

battalion, who had enlisted at Kingston Ontario, in 1914, and “rose from the

ranks” to become an officer. Like many members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force,

he had moved to Canada from Great Britain. Except for Jones, Hill 70 would be the

cadre’s first major operation. On the 15th of August, the 21st Battalion’s

assigned objective was the capture of two sets of German trenches in the rubble of the

suburbs of Lens, just south of Hill 70. Although the 21st was not a Highland Battalion, it

“went over the top” at 4h25 to the sound of its pipe band. As planned, the

musicians soon exchanged their pipes for stretchers. All the objectives were captured with relatively

few casualties. However, a sniper killed Lt. Mowat soon after the start. There was a lull in the fighting after this, so

the men, under the direction of their officers, busied themselves by consolidating their

new territorial gains, in preparation of the inevitable German counter-attack. Spirits

must have been high as soldiers fumbled with entrenching tools, filling sandbags that were

vital to the consolidation. Wrecked parapets were repaired and the trenches modified to

suit the new occupants. The problem with captured trenches was that they always faced the

wrong way! All this occurred at a feverish pace: everyone

knew that the Teutonic retaliation would be brutal and determined. After all, Haig had

warned Currie: “They (the Germans) aren’t going to let your have Hill 70.” Throughout the day the Germans attempted to

dislodge the new “Kings of the hill” and a ding-dong struggle ensued,

highlighted by many German counter-attacks. It must have been quite chaotic for both sides of

the chessboard due to the terrible noise, the poison gas, the blood. To make matters

worse, German planes entered the fray attacking the Canadians and causing many casualties.

While skillfully disposing his men and repelling

one of these German counter-attacks, Lt. Irwin was wounded in the abdomen and forehead. He

managed to rally his men and repelled a second attack before being evacuated. During the pandemonium of the 15th, Lt. Jones was

shot in the right leg and evacuated, leaving Lt. Govan in command of what was left of

“C” company. For two more days the Germans attempted to

dislodge the Canadians from Hill 70. On the morning of August 17, the Germans launched

another determined attack from a communication trench on the 21st battalion front. The

enemy was again repulsed, but not before Lt. Govan was dangerously wounded in the abdomen,

leg and arm by shrapnel from the explosion of a hand grenade. He was evacuated to Casualty

Clearing Station 23, near the front— where he died on August 28. A witness wrote to Mrs. Govan after the battle: “The Canadians took their objective, Waltie

leading his own platoon and held it against eight counter-attacks of the Huns. Those

counter attacks are really harder to hold out against than it is to take an objective. It

was in one of these attacks that Waltie received his wounds. It was fought at close

quarters, almost had to hand, within bomb throwing distance of one another, and the way

Waltie carried on and the example he set his men would do your heart good, to hear the way

his men speak about his actions. He was actually a prisoner in German hands, owing to

superiority of numbers but at the critical moment our reinforcements came up and he fought

his way clear. The Huns seeing our assistance coming, retreated on the run, but before

doing so threw the bomb that wounded poor Waltie. He was carried out and had his usual

little smile on his face and seamed quite satisfied…Major ??? told me to tell you

that Walter was recommended for the MC (Military Cross). It had left our Batt (Battalion)

and gone to Brigade but he died before it went through.” The Canadians held Hill 70 and Haig’s

objectives for the battle were met. The Canadians had inflicted heavy casualties on the

Germans and prevented the movement of reinforcements from the Lens sector to Flanders. I have recently visited Hill 70, a bit of high

ground between the cities of Loos and Lens, France, with a group, including the grandson

of Masumi Mitsui, a Canadian soldier who earned the Military Medal for bravery at Hill 70.

I found it sad for Canada that no monument, public or private, commemorating the

battlefield. If there was one, maybe the inscription could

read: On August 15, 1917, the Canadian Corps, through a

remarkable feat of arms, captured and held this height. The British army fought a bloody battle on this

same piece of ground in September 1915, as part of the battle of Loos. Lt Donald Cameron

Deford MacMaster, also a former member of Govan’s congregation, was killed there on

September 25th 1915, while serving with a Highland battalion of the British Army.

(Macmaster is commemorated on the family headstone near the entrance to the church, near

the Govan’s.) Postscript Lt. Irwin was awarded the Military Cross for his

gallantry at Hill 70. Lt. Mowat’s body was lost in the chaos of

war. His name is commemorated on the Vimy Memorial, which acts as Canada’s monument

to the missing in France. A few years ago, Norm Christie, author and host of the

television series For King And Empire, which airs on history television, came across some

burial records referring to a group of unknown 18th and 21st battalion soldiers resting at

Cabaret Rouge Cemetery near Vimy. The six soldiers had been discovered in a shallow grave

in 1924, near the spot where the 21st battalion began

their attack on August 15th, 1917. The burial officer was only able to identify one body:

20-year-old James Henry Tyo of Cornwall. All were exhumed and re-interred in Cabaret

Rouge. Christie discovered that one of the unknowns was from the 21st battalion, and that

he was shod in officer’s boots when he was exhumed. This was enough evidence to

identify the remains as those of Lt. Grant Davidson Mowat, the only 21st battalion officer missing after the battle. His head stone

has been replaced by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission with a new one that reflects

his true identity. Lt. Jones and Govan of “C” company and

other officers were mentioned in the unit’s war diary for their work and initiative.

Following this, the author offered the following statement: “There were many outstanding acts of bravery

and the decorations awarded represented a small percentage of these.” With respects to Govan’s performance, the war

diary further states that: “Lt. Govan will be remembered as a brave

leader always concerned with the welfare of his men.”

He is interred at Lapugnoy Military Cemetery, near

Bethune, France and commemorated at St-Andrews cemetery, Williamstown Ontario. (This story first appeared in "The Maple Leaf", the newsletter of the Central Ontario Branch of the Western Front Association, COBWFA. It is reproduced here with the permission of Glenn Kerr, the editor of The Maple Leaf, as well as the author, Michel Gravel. The transcription was done by John Sargeant and the photos were added by the webmaster. The webmaster would like to thank Peter Gower for supplying the photo of the medal on display in the church.) Thanks to Bill Cattanach for the photo below of the family plot in the St Andrews United Church Cemetery in Williamstown Ontario |

|

2010

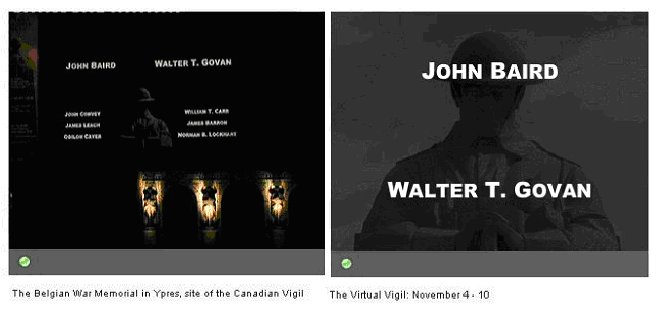

For the 7

nights leading up to November 11, 2010, the names of all Canadian soldiers were projected

onto the Belgian War Memorial in Ypres. At

the same time, the same names were being broadcast via the internet to schools across

Belgium and Canada. The image above shows

the opening ceremonies at the Belgian War Memorial on November 4, 2010. Below on the

left is the name of Walter Govan being projected on that wall. Below right shows the name being broadcast to the

schools. Each name appeared for 25 seconds

and each night 9,700 names were shown.

|